(RE)WIRING THE (HI)STORY: NINA IVANOVIĆ

I'm drawn to the contrast between fragility and strength, when something appears delicate but is, in fact, resilient, or the other way around. This tension, where appearances can be deceiving, continues to intrigue me.

Nina Ivanović

She creates photo diaries: wherever she travels, she collects images that become a personal archive of memories. Nina Ivanović, an artist, sculptor, and photographer, travels a lot: through exhibitions, residencies, or with her U10 collective. These photographs form the foundation of her work, a visual memory bank she revisits whenever preparing new projects or exhibitions.

For Nina, walking, roaming, and exploring is an essential part of her creative process. Moving through spaces shifts her perspective and allows her to observe and learn, shaping the way she works.

She primarily uses an analog camera, later scanning the photographs. The limitations and structure of analog photography appeal to her, from controlling light and shutter speed to the tactile quality of the final image. While digital photography offers endless possibilities with a simple click, Nina prefers analog for its intentionality and the aesthetic it produces, even though she admits it can be expensive.

Photographs have always played a role alongside her other media. In her early work at the faculty, she combined photographs with sculptures in small pieces, exploring the interplay between mediums. Her first exhibition included sculptures, photographs, and drawings, reflecting a parallel practice across different forms. Over time, however, she began to separate them: exhibitions of photographs became exclusively photographic, while sculptures and drawings remained distinct. The choice depends on the topic, the exhibition space, and what she finds compelling to explore in each material at any given moment.

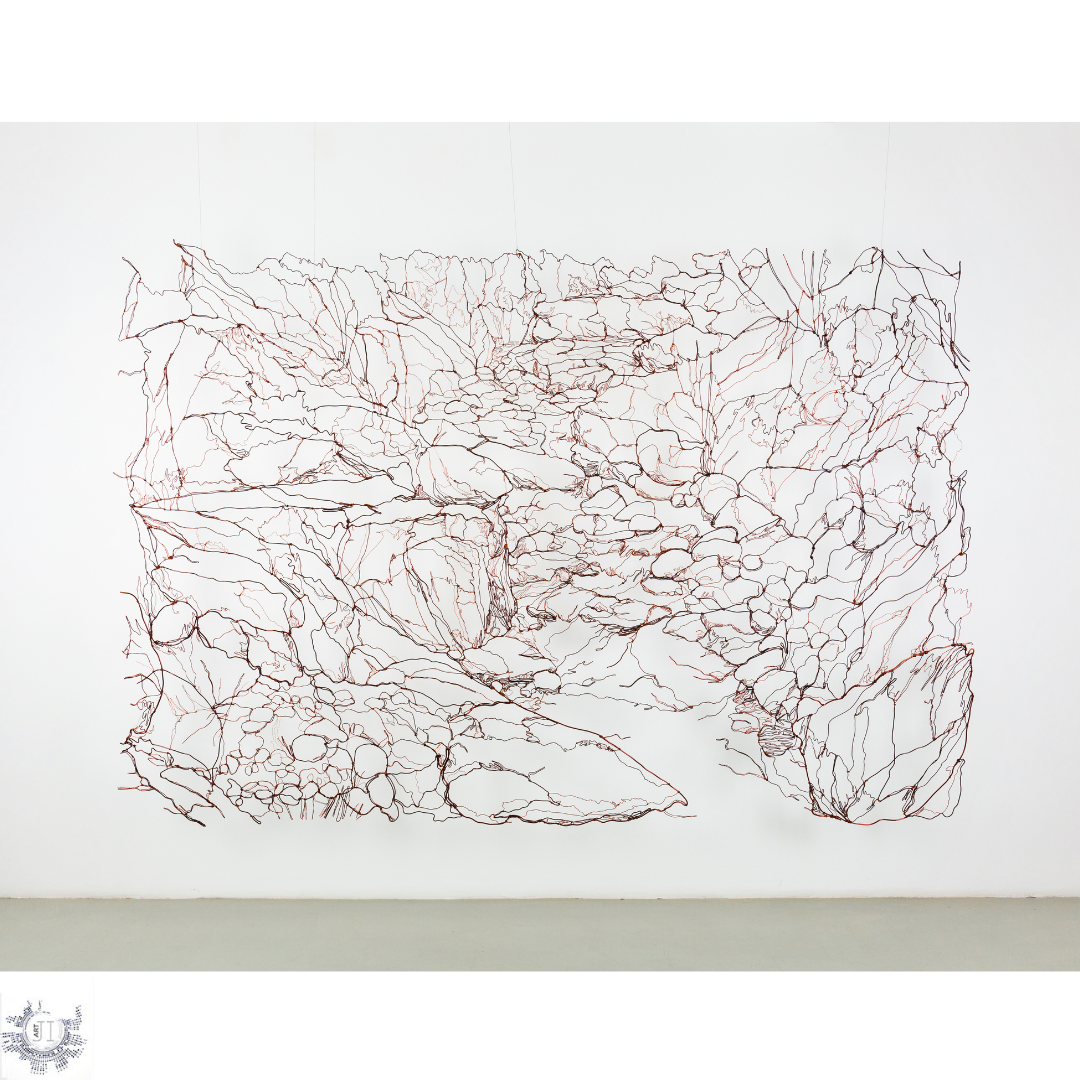

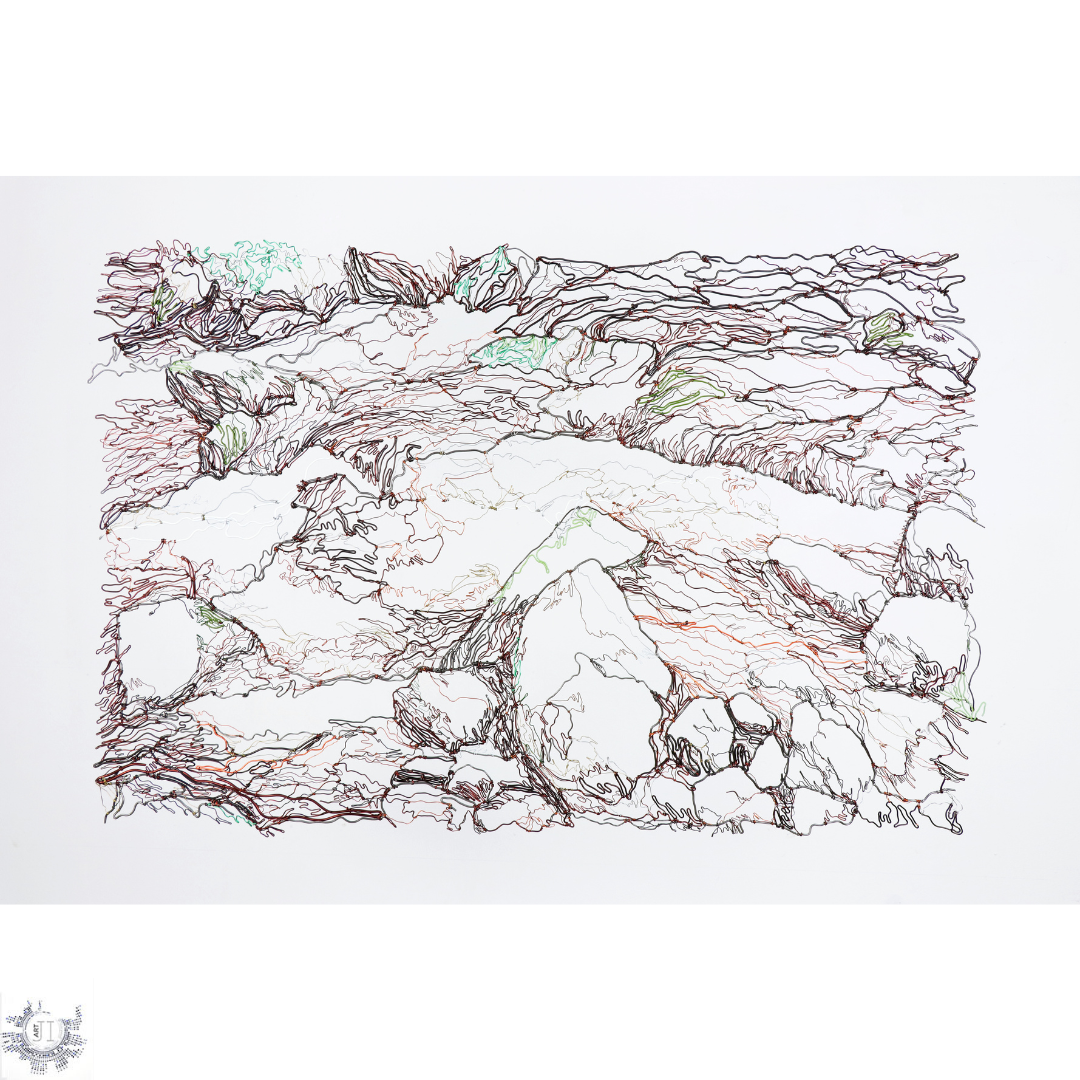

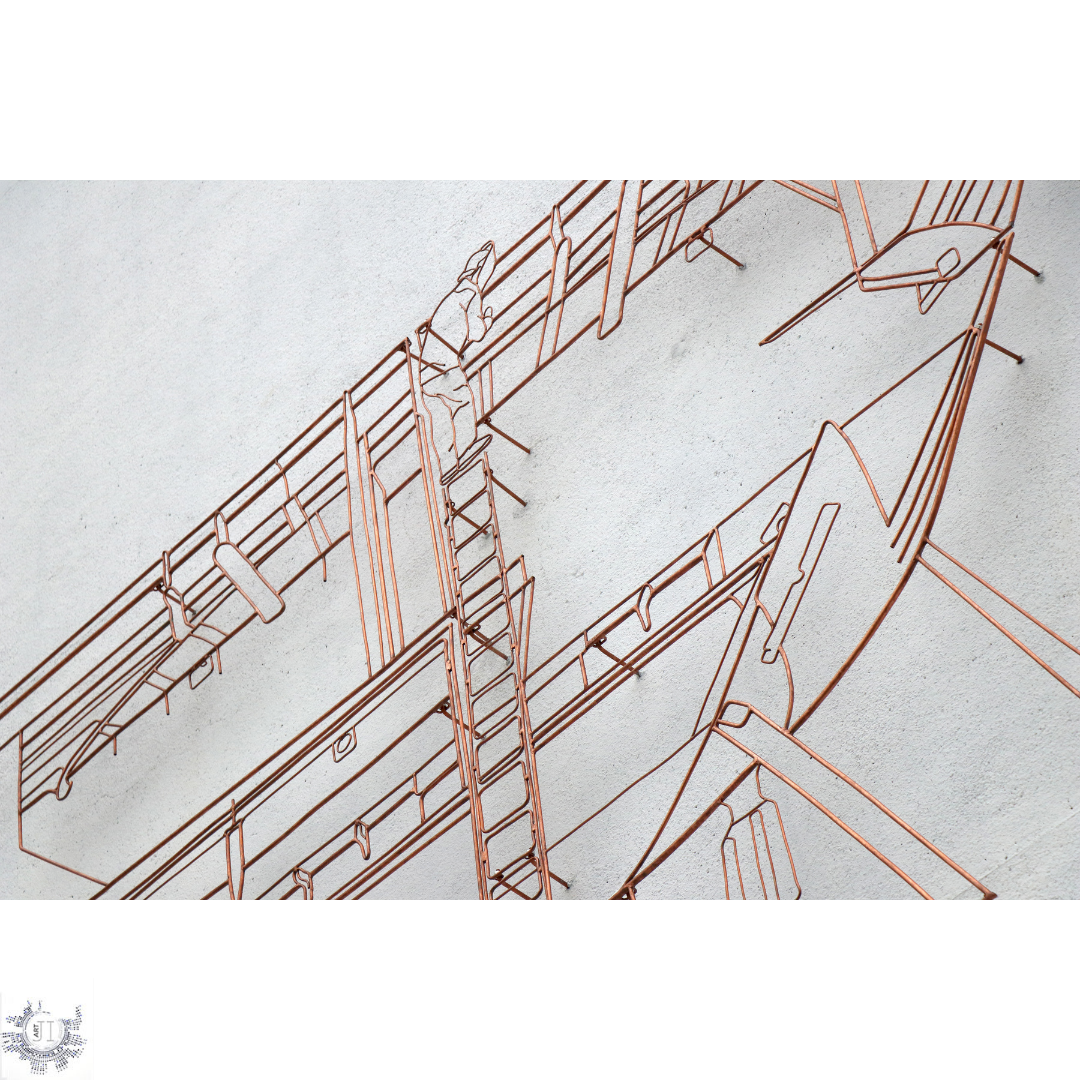

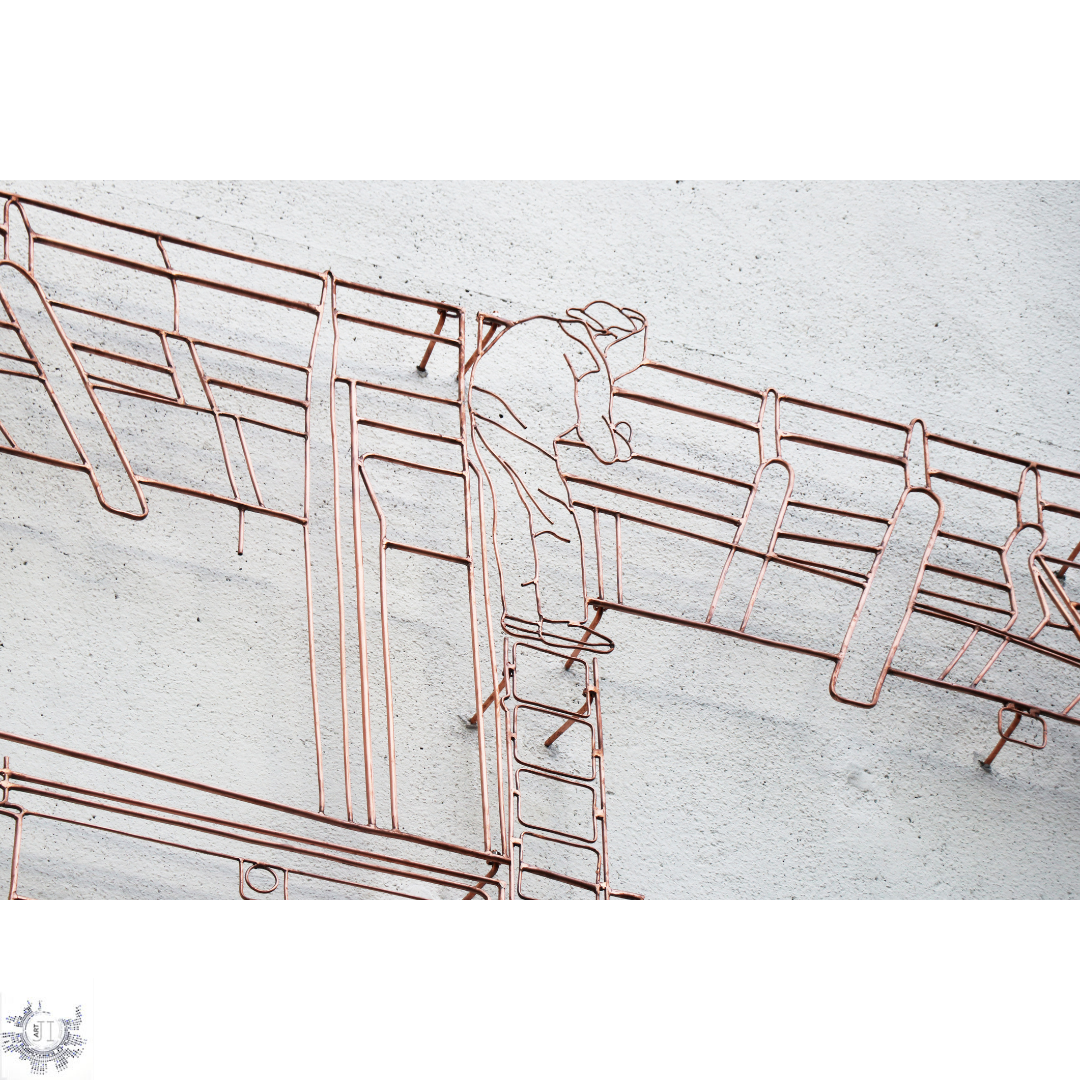

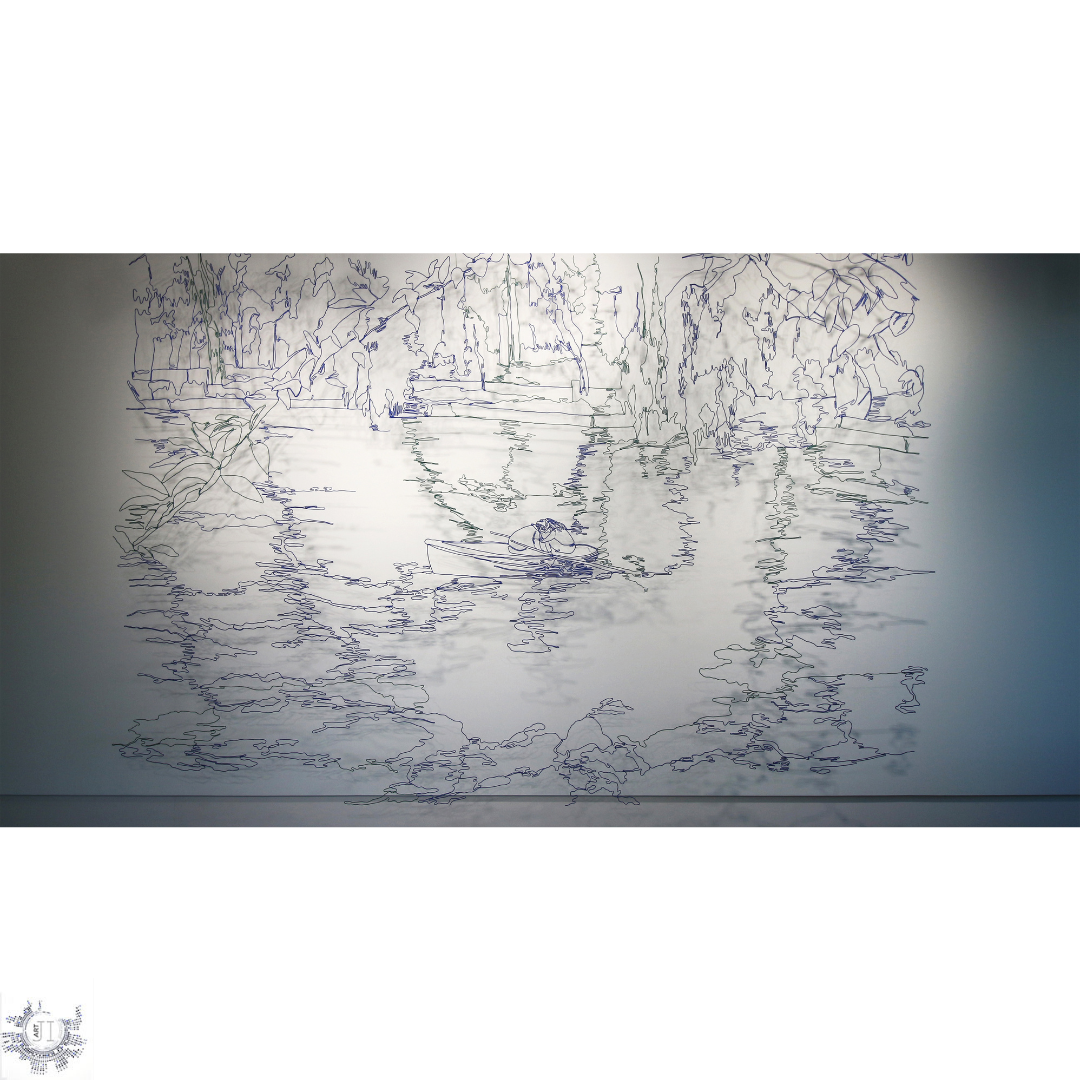

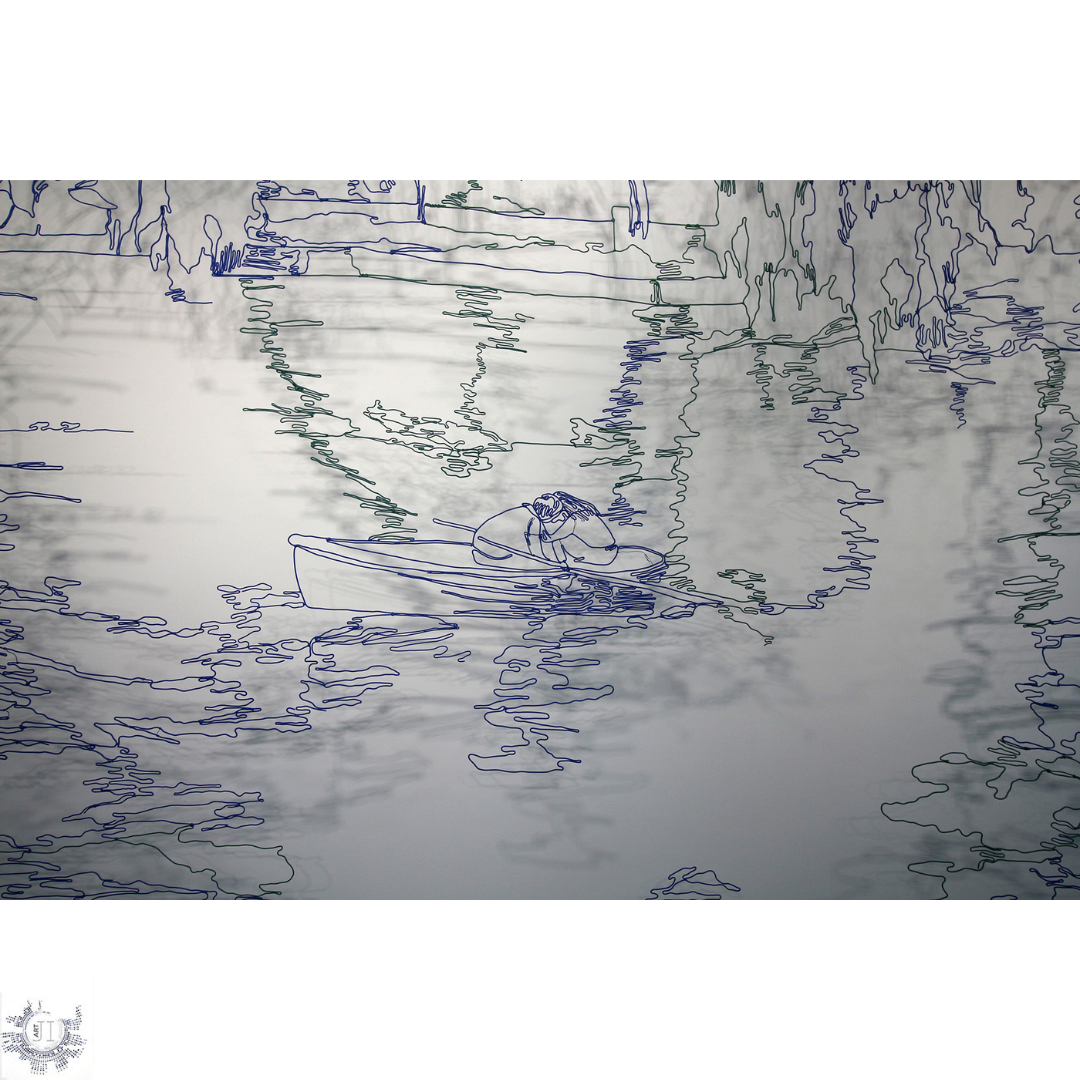

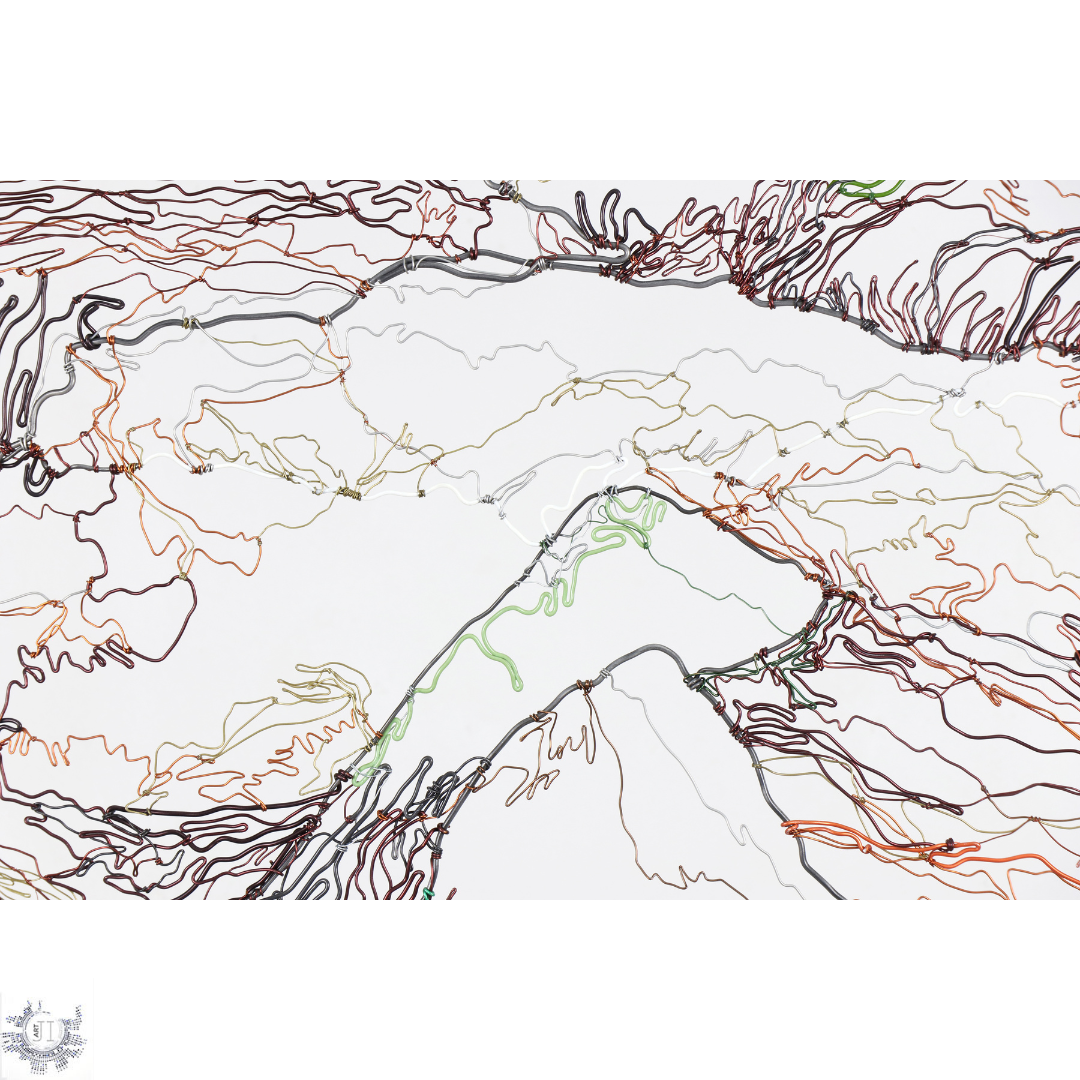

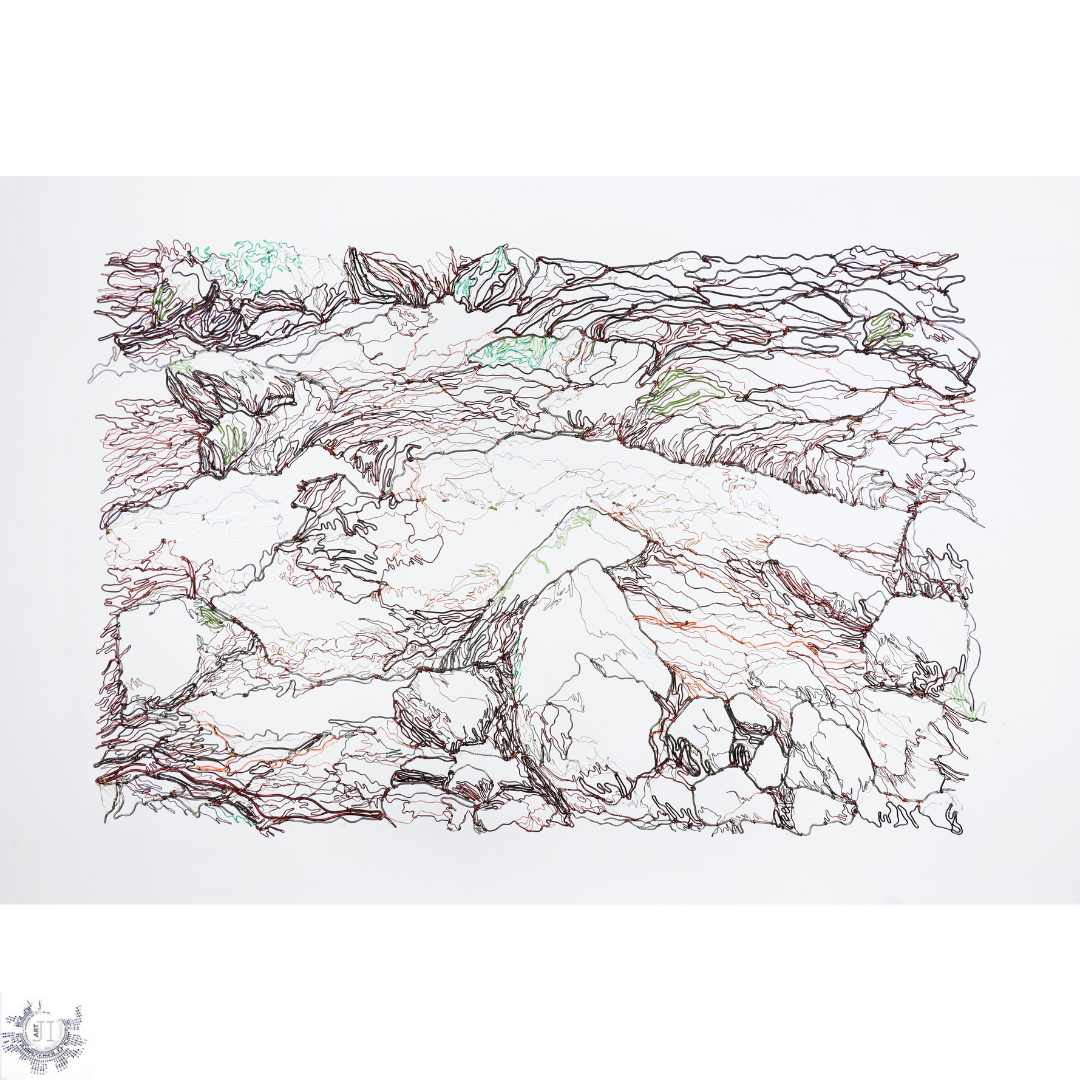

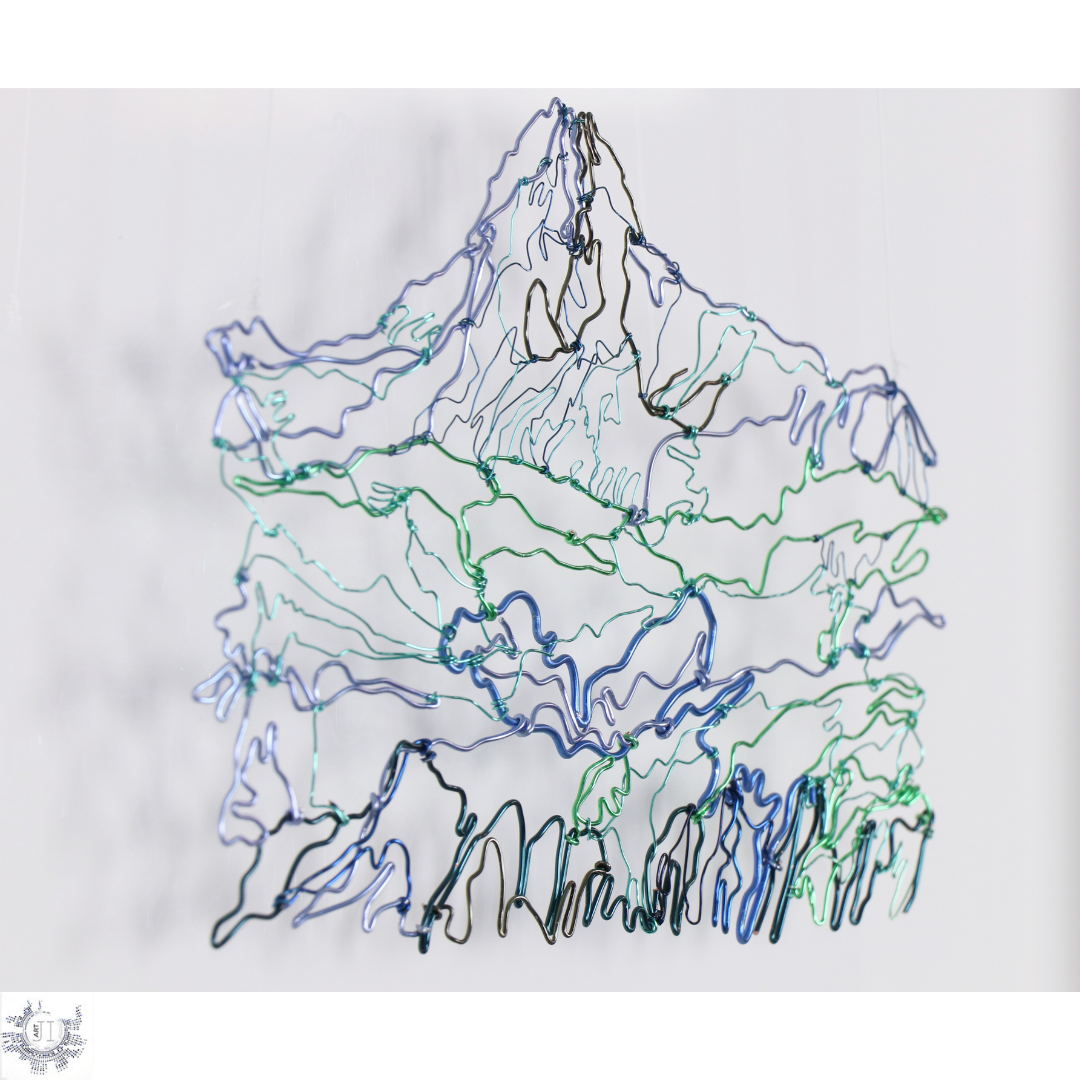

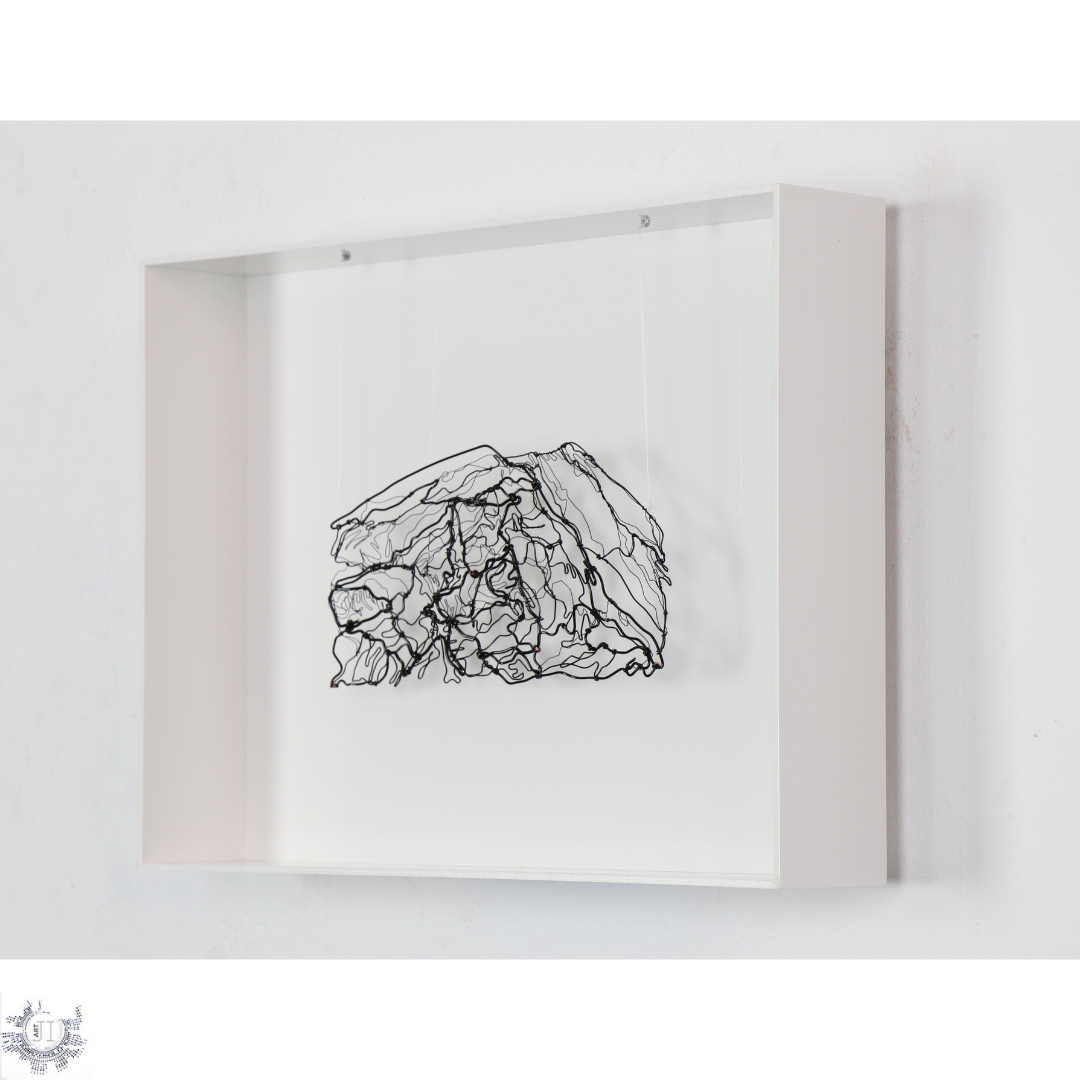

In recent years, Nina has become widely recognized for her wire sculptures and spatial wire drawings, where line, light, and shadow merge into delicate, powerful compositions. Working with wire and metal rods, materials that are at once fragile and resistant, she explores the tension between delicacy and strength, between what seems ephemeral and what endures.

Each installation begins as a drawing on paper and gradually transforms into a three-dimensional composition. Within this process, gesture and spontaneity coexist with precision and control. Nina embraces so-called ‘errors’ as part of the creative act, seeing them as opportunities to find new solutions through material and form.

Viewer perception is also integral to her wire work. Light, shadow, and movement continually reshape how a piece is experienced, and she often adapts her installations to the specific qualities of each space.

We have discovered Nina's wire sculptures at Vienna Contemporary and were incredibly lucky to interview the incredible and unusual artist after the exhibition.

What I like the most, particularly with spatial wire drawing, is that I strip away all volumes and reduce form to a simple linear language, similar to handwriting.

Nina Ivanović

The JI: Your work often sits in the borderlands between drawing and sculpture, or between spatial form and representation. How do you perceive that boundary: is it something you seek to transcend, maintain, or question? What does meaning live in: in the crossing of boundaries, or in their tension?

Nina Ivanović: I studied painting at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Belgrade where there is a tradition of nurturing drawing, whether as a sketch for developing ideas, for larger projects, or simply as an independent form. Also, I enjoyed working with clay and other materials in the sculpturing department, so it felt natural for me to combine these visual languages: drawing, sculpture and photography. I don’t necessarily see boundaries between these different expressions, they are intertwined. But what I like the most, particularly with spatial wire drawing, is that I strip away all volumes and reduce form to a simple linear language, similar to handwriting.

I prefer to leave it up to the viewer to sense whether a work is connected to the past, the present, or the future. After all, history tends to repeat itself.

Nina Ivanović

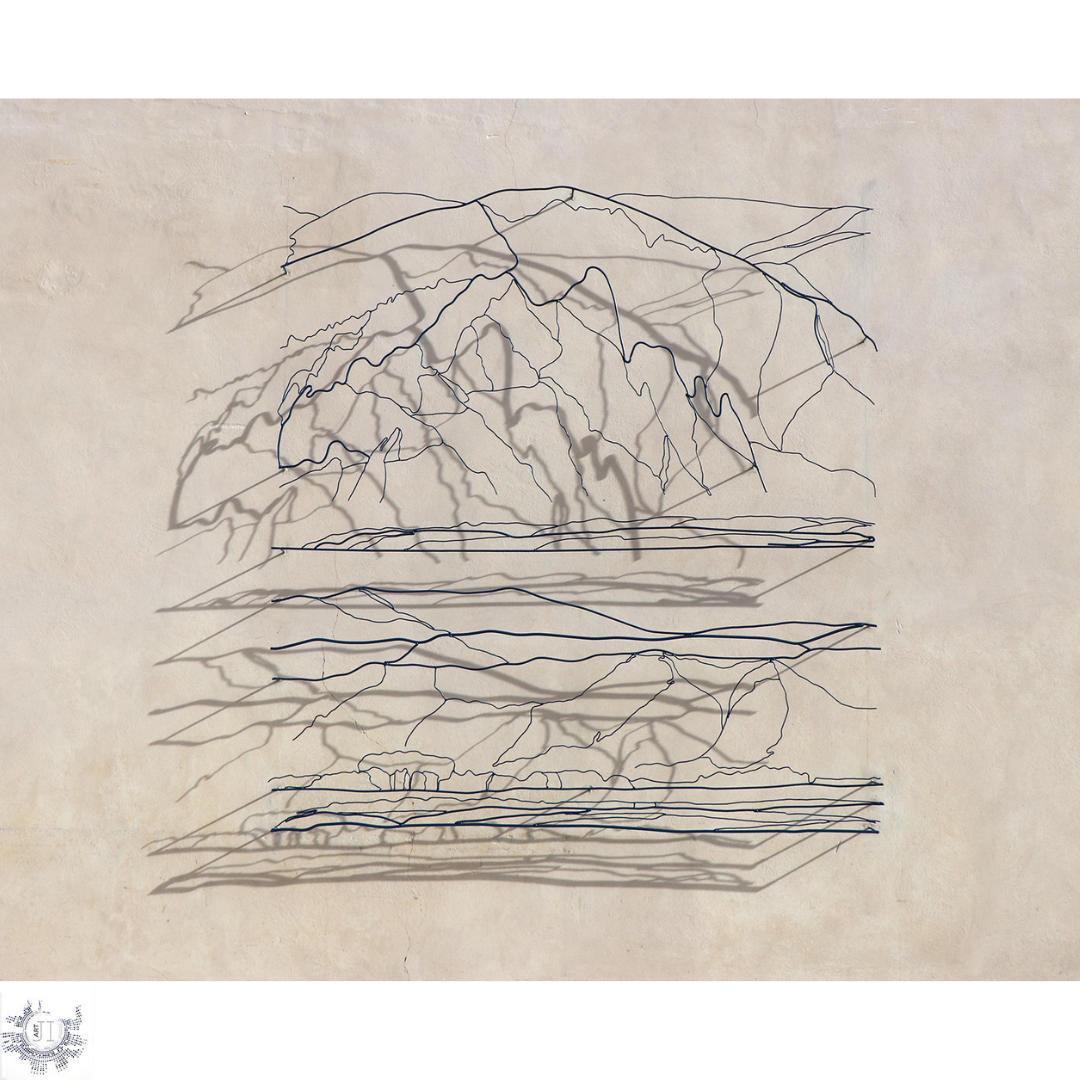

The JI: You use photography to capture fragments of visual memory which you later materialize through wire or drawing. What is the role of memory in your creation: do you see your art as resurrecting what was, or imagining what could be?

Nina: For me, drawing something is a way of learning about it. It requires time, observation, and attention to detail. Photography, on the other hand, captures a moment instantly. Later, when I go through the scanned files (I prefer using 35 mm film cameras), I begin to create stories from them. It is about observing and noting interesting or absurd situations, striking landscapes, and so on.

So to answer, yes, memory is an integral part of the process. But I prefer to leave it up to the viewer to sense whether a work is connected to the past, the present, or the future. After all, history tends to repeat itself.

The JI: Many of your installations and spatial drawings use wire forms that are sharp, fragile, sometimes ephemeral. What is the relationship between what holds form and what risks collapse? Do you think art must risk fragility?

Nina: I definitely appreciate the presence of fragility in certain works. At the same time, I often work with wire and metal rods that are rigid and difficult to bend, resulting in works that can feel resistant, strong, and even slightly dangerous, especially if a viewer accidentally brushes against one of the free-floating lines of the sculpture.

The character of the material plays an important role, some metals are softer and more pliable, while others demand considerable physical effort to manipulate. I'm drawn to the contrast between fragility and strength, when something appears delicate but is, in fact, resilient, or the other way around. This tension, where appearances can be deceiving, continues to intrigue me.

The JI: You’ve made works in public facades, in galleries, residencies, as well as more intimate drawings. How does context – whether it is meant for a public architectural surface, or a gallery, or a personal sketch – change what you intend?

Nina: I wouldn’t say it changes my intention, in fact, it’s the most important part of it. When creating a work for a public space, I plan carefully, considering the surface it will occupy, its location, the occasion, and of course, the budget. All these factors are integral to the process, and I genuinely enjoy this aspect of creating for public spaces. It involves a lot of planning, but it’s a rewarding process.

For art residences, my work is always a reflection of what I absorb from the location. Whether I’m photographing or drawing everyday urban situations or landscapes, learning about history, architecture or geography of the place… the work is deeply connected to that specific place.

The JI: Given your practice with materials that may age, wires that may shift, memories that fade, how do you think about time in your work? Is permanence something you aim for, or something you accept the impossibility of?

Nina: Aging, fading and shifting is a part of life 😊

The JI: You co-founded U10 Art Space, organize exhibitions, etc. How do you see your identity as an artist vs an organizer vs a curator vs a community-builder? How much of your practice is about your private creative impulse versus the social responsibility of creating a space for others?

Nina: Co-founding U10 in 2012 was a very significant moment for me and my colleagues. Originally conceived as a short-term project where we could exhibit our work, it has grown into a 13-year-long program open to diverse artistic practices, with a focus on younger artists who are just beginning to develop their exhibition practice.

It is a project that relies on private funding for its basic operations, while the rest is supported by the U10 collective, the artists themselves, and, when available, public funding. Our country is currently facing a crisis, and this is strongly reflected in the cultural sector, to the extent that we’re uncertain whether there will be any cultural budget at all this year. These budget cuts further destabilize the already precarious position of artists in our society.

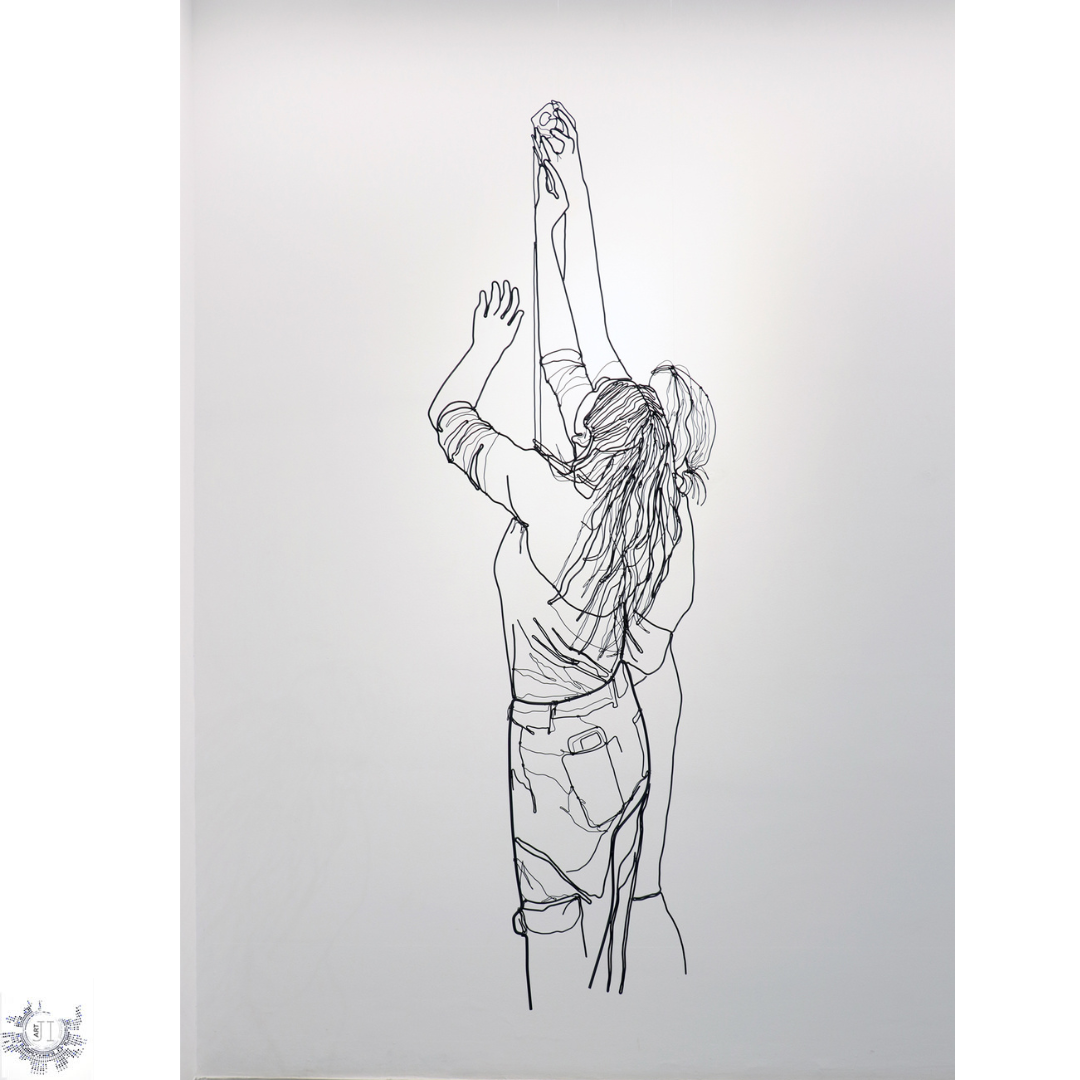

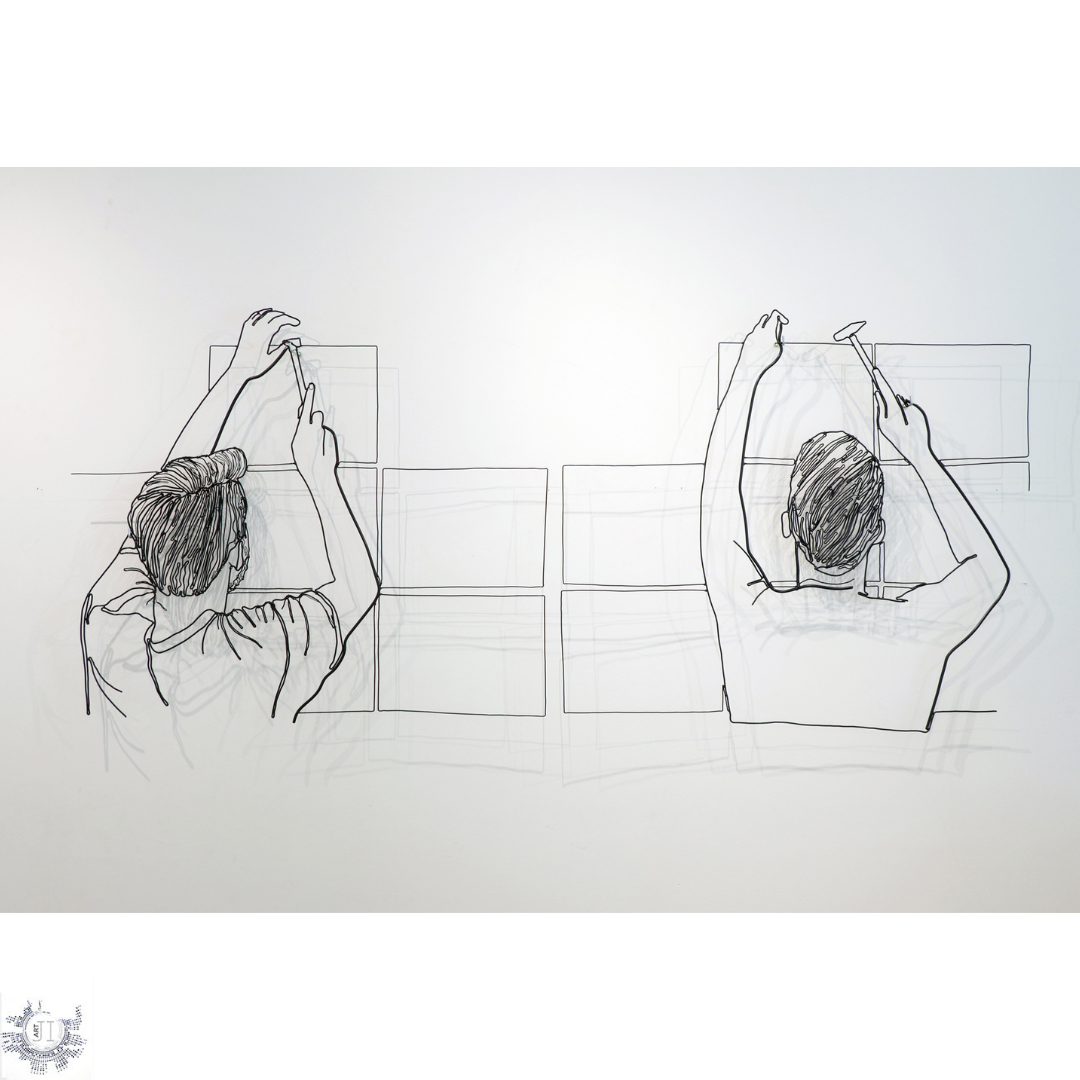

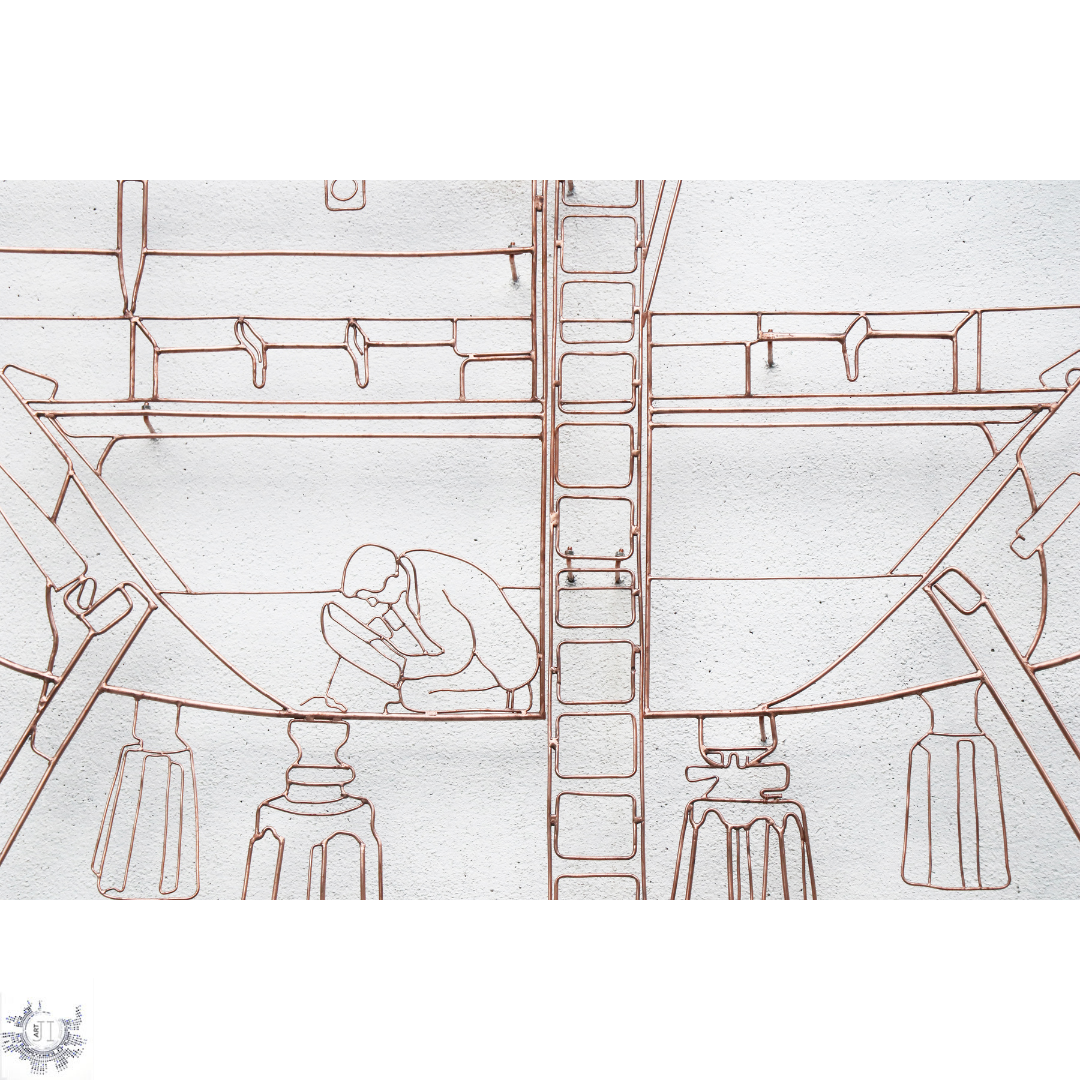

My connection to the U10 can be seen through my last show, which was about togetherness and being part of an art collective. It was titled Setup, and here is an excerpt from the text written by Sanda Kalebić, who is also a member of the collective:

Nina’s works produce a visual narrative of the process in which an exhibition is made. They single out moments of collaboration, of group endeavors and unity – frequently some of the most beautiful moments in the entire process of the realization of a show. As a member of an U10 art collective in Belgrade which, at least in our conditions, has a lengthy continuity, Nina has had opportunities to observe directly the experience of collective activities at hundreds of exhibitions and thousands of moments that sublimate the essence of togetherness. Her archive, as well as the whole archive of U10, grown from closeness and participation, refers to formal collectives, informal groups and friendly networks of joint assistance spontaneously informed during the show setups.

Sanda Kalebić

The JI: What does ‘authenticity’ mean to you in the making of art? Is it in the spontaneous gesture, in the planning, in the visible process, or in the invisible? Do you prefer that viewers see traces of struggle, error, or polishing? How do errors and accidents enter your work, and do they remain in it?

Nina: When it comes to wire installations, there is a planned process involved. I usually begin by preparing what I want to create and drawing it on paper. Then, in the process of working with wire, I rely on gesture and spontaneity within those controlled conditions.

Also, I wouldn't call anything in art an error. I gladly include “errors” as part of the work. Sometimes it might not be possible to realize exactly what you initially imagined, but there is a certain beauty in finding new solutions, whether through different approaches, materials, or techniques. Precision in art is what the artist makes of it, it's beautiful because you’re the one setting the rules and playing with their meaning.

Precision in art is what the artist makes of it, it's beautiful because you’re the one setting the rules and playing with their meaning.

Nina Ivanović

The JI: How much of your work is driven by inner emotional, psychological landscapes – desires, conflicts, fears, versus external observation of forms, architecture, nature, urbanity?

Nina: I am very much driven by external observation. But I think that the subject of a work, how it is shown and where, what material is used and in what way, can show someone’s inner (as you say) landscape.

The JI: When you create work based on delicate or ephemeral materials, or with minimal visible mass (wire, lines, shadows), to what extent are you aware of the viewer’s perception: light, shadow, angles, distance? Is the viewer’s movement, angle, participation part of the work? How do you want your audience to move around, see, maybe even mis-see your pieces?

Nina: Viewer perception is for sure part of the work. The viewer’s curiosity, their interests, and ultimately the way they move around the work is an integral part of it. I am aware of the potential that light and shadow have in shaping the perception of spatial installations, so I tend to use them in the best possible way depending on the space and its possibilities.

Some works demand a great deal of time, and during that process if the conditions are good – you have a studio, time and the budget – you can set aside the challenges our society faces and immerse yourself in the delightful absurdity called art.

Nina Ivanović

The JI: In times of social change, environmental concern, political turbulence, do you see your artistic practice as having an ethical dimension or responsibility? How do you situate your art in relation to crises, whether ecological, sociopolitical, or personal? Is art, for you, a mode of reflection, resistance, comfort, or something else?

Nina: I don't think it's adequate to comment on whether my artistic practice has an ethical dimension or responsibility. My interests range from the purely aesthetic beauty of natural landscapes (which are of course endangered), then capturing people engaged in everyday activities, to some research that delves into the problems of current society, such as river pollution... It is again in the eye of the beholder to decide if work has revealed some new perspective on specific matters or just made something visible, whether it’s about social or ecological problems.

What matters most to me is that the subject I’m working on is meaningful. More often than not, it reflects my environment, so it naturally varies over time. At the moment, for example, Serbia is witnessing large student protests that are reshaping our social reality and giving hope for profound change. These moments inevitably influence the way I think about art and its place in the world.

The creative process encompasses all of this: reflection, a degree of resistance, and ultimately, the satisfaction of being able to research any topic that interests me. Some works demand a great deal of time, and during that process if the conditions are good – you have a studio, time and the budget – you can set aside the challenges our society faces and immerse yourself in the delightful absurdity called art.