WHERE DREAMS REMEMBER THEMSELVES: INSIDE THE MIND OF ALEXANDER KRYZHANOVSKYI

Symbolically, my work explores contrasts and variations in the human image. I depict humans both as small, individual beings and as part of a collective history – employing sacred and iconographic approaches that present the human as a macrocosmic and microcosmic element, reflecting both the spiritual and material order on earth.

Alexander Kryzhanovskyi

At just twenty-eight, Alexander (Oleksandr) Kryzhanovskyi has already established himself as one of the most intriguing voices in Ukraine’s contemporary art scene.

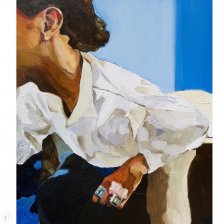

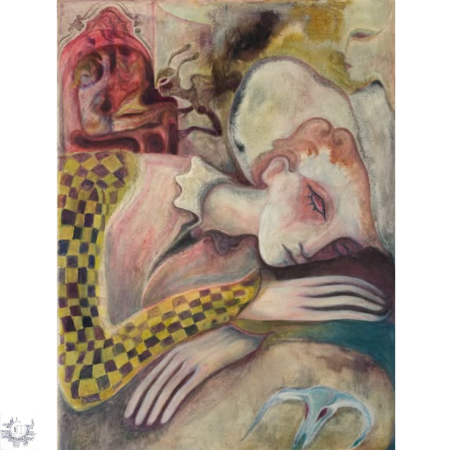

Based in Kyiv, the multidisciplinary artist works across painting, graphics, and sculpture, weaving together fragments of memory, dream, and personal mythology. His paintings, filled with vivid colors, fractured figures, and abstract architectures, feel like scenes glimpsed in a half-remembered dream, at once personal and universal.

Born in Drohobych, in western Ukraine, Alexander came to art through philosophy and literature. Influenced by the great thinkers such as Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, and guided by his mentor, the late painter Serhiy Matyash, he began to develop a practice that treats art as both introspection and social reflection. His creations are deeply concerned with the condition of the individual in a time of historical rupture: the so-called rift between the inner and outer worlds, the psychological and the material, the subconscious and the rational, where much of human conflict and creativity originate.

That sense of duality runs through all his work. Alexander's simplified, almost cubist compositions challenge the dominance of excessive rationality, while his use of symbolism invites to read each painting like a coded narrative of identity, trauma, and renewal.

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, his reflections on conflict, belonging, and transformation have gained new urgency. Participation in the major exhibition “How Are You?” (Ти як?) at the Ukrainian House in Kyiv placed Alexander among a generation of Ukrainian artists redefining what art can mean in wartime: artists who confront catastrophe not through propaganda or despair, but through an insistence on humanistic and metaphysical depth.

In our interview, Alexander Kryzhanovskyi speaks with lucid honesty about the evolution of his artistic language, the interplay between personal and collective identity, and the moral responsibility of art in an age of instability. What emerges is a portrait of an artist who approaches creation not as an escape from reality, but as a method of understanding it, where every line and color become a record of consciousness itself.

In some of the most mysterious dreams, I see my hometown as if it were medieval, with wooden houses and uninhabited panoramic landscapes. Or I see a huge monument of Mercury in the main square, and instead of the city hall there’s a stele – and all of it is filled with dramatic or surreal scenes in which I am both the main character and an observer of archaic essence of an unknown dimension revealed to me through the place where I grew up.

Alexander Kryzhanovskyi

The JI: Many of your works draw on personal memory and dreamscape, forming what’s been called a “personal mythology.” Could you walk me through one or two of your recurring symbols? Where did they first appear in your life or art, and how have their meaning shifted over time in your work?

Alexander Kryzhanovskyi: I really do turn to dreams in my work – perhaps it’s the only theme that connects to my experience and personal life directly, rather than indirectly, as happens more often in painting or sculpture.

One of the most recurring symbolic images in my dreams is my hometown – Drohobych, in the Lviv region – which has appeared in my dreams dozens of times over the past eight years. Its symbolism lies in the way it appears: through fragments of architecture, sometimes landscapes or streets, or even mythological images. These recurring elements show me not the town I know, but something from a completely different angle of perception.

For example, in some of the most mysterious dreams, I see my hometown as if it were medieval, with wooden houses and uninhabited panoramic landscapes. Or I see a huge monument of Mercury in the main square, and instead of the city hall there’s a stele – and all of it is filled with dramatic or surreal scenes in which I am both the main character and an observer of archaic essence of an unknown dimension revealed to me through the place where I grew up.

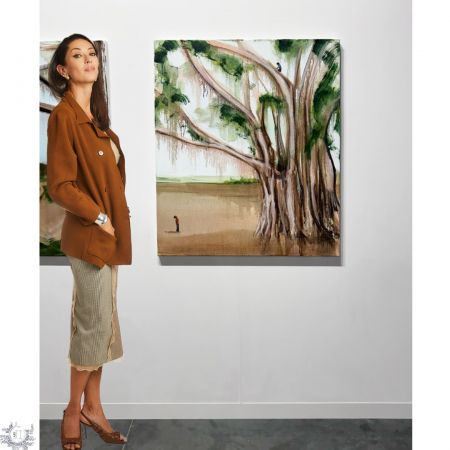

Another symbol I use in my work is the human figure. It is the person who brings each of my works to its conclusion and, in a way, accompanies me. Symbolically, my work explores contrasts and variations in the human image. I depict humans both as small, individual beings and as part of a collective history – employing sacred and iconographic approaches that present the human as a macrocosmic and microcosmic element, reflecting both the spiritual and material order on earth.

Through the history of humanity, or of particular territories, we can trace how, over time, the vectors, goals, and methods of destruction – by which humanity destroys itself – change. This forms the first part of my critical perspective on existence.

Alexander Kryzhanovskyi

The JI: Your work often examines the individual as a social unit. How do you see your own identity, in terms of nationality, culture, generation, shaping your art? Are there tensions between personal and collective identity that you try to capture?

Alexander: In my work, I oppose the individual as an external social being, living within a rationally established, visible, practical order, which exists in conflict with archaic forces, archetypes, and the subconscious. I call this a rift, which separates the world of causes from the world of consequences, and it is this rift that generates numerous cataclysms and traumas of varying degrees. Through the history of humanity, or of particular territories, we can trace how, over time, the vectors, goals, and methods of destruction – by which humanity destroys itself – change. This forms the first part of my critical perspective on existence.

The second part approaches this issue by showing that these rifts in history are filled with experience and memory, from which universal human values, traditions, self-awareness, and ultimately identity and a sense of belonging are formed.

For me, personal and collective identity are deeply intertwined, as I feel a profound connection to Ukraine. Through this bond, I experience a deep sense of support, understanding, and alignment with my ideas, goals, and aspirations.

Perhaps in my practice, I aspire to avoid conflict with myself – and this is only possible when the collective and personal components can interact, find a way forward, and eventually converge over the course of life. Of course, this may sound somewhat idealistic, since uncertainty and disorientation are characteristic of our time. That is why I feel joy when I am at least occasionally able to notice a ray of convergence between the categories of personal and collective identity.

I was invited to a major exhibition in 2022 at the Ukrainian House in Kyiv. This was an extremely important event with a fragile title, “How Are You?” (“Ти як?”), because at that time it was used not only to ask about the well-being of a friend or acquaintance, but also, unfortunately, as a way to check whether someone was alive and safe.

Alexander Kryzhanovskyi

The JI: Given the situation in Ukraine, how has the war, displacement, or political instability affected your artistic practice: not just the content of what you make, but your process, materials, daily rhythms, and how you think about what art can do?

Alexander: When the full-scale invasion began, I was in Kyiv with my friends. There was no time to analyze or reflect – everything was clear once you've woken up to explosions and air raid sirens. I needed to be decisive, stay in touch with family and friends, understand how to act next, and try to help those who needed it.

Since I was born in Western Ukraine and lived in Lviv at the time, I didn’t need to relocate, but we welcomed many people into our home who were fleeing from Eastern Ukraine to safer regions. The political situation was clear: the government and the population had to confront numerous challenges and fight to preserve statehood and identity. Many rules and laws were adjusted to regulate the situation and prevent chaos within the country. During the first months, I did not work in my studio – it became secondary for several reasons. Most of us hoped the full-scale invasion would end as abruptly as it had begun in 2022, but it did not. The invasion continues, and we continue to lose those closest to us. This is reality, and it leaves a lifelong mark.

After some time, I created a few drawings and was invited to contribute to a major exhibition called “How Are You?” (“Ти як?”) in 2022 at the Ukrainian House in Kyiv, which included works by over a hundred Ukrainian artists. This was an extremely important event with a fragile title, “How Are You?”, because at that time it was used not only to ask about the well-being of a friend or acquaintance, but also, unfortunately, as a way to check whether someone was alive and safe.

Participating in that exhibition and meeting new people created a certain stimulus for my work. I began working again, continuing to experiment with ceramics and graphics, and exploring important questions through the lens of art – which, for me, is the most essential tool for understanding the world. Later, I moved to Kyiv, where I now live and work.

I cannot fully reflect on this yet, because when I start thinking about my experience, I realize that this is still my present life – the full-scale war has been ongoing for more than three years. Any attempt to describe its effects now would feel incomplete; it will only become clear once the war ends and recedes into my past.

Alexander Kryzhanovskyi

With the full-scale invasion, everything in my life changed, because I am a young artist who had no idea what war was – and it happened. Most of us cannot simply immerse ourselves in the flow of global art; we constantly have to be aware and do something that can help friends in the military or friends who have suffered loss.

Unfortunately, I cannot fully reflect on this yet, because when I start thinking about my experience, I realize that this is still my present life – the full-scale war has been ongoing for more than three years. Any attempt to describe its effects now would feel incomplete; it will only become clear once the war ends and recedes into my past.

Currently, my process is well established. I am working on a series of paintings and creating ceramic sculptures, and my materials remain unchanged.

When it comes to what art can do, I find it especially valuable to exchange thoughts with my friends from different fields. We share ideas, combine our approaches, learn from each other, and move forward. I believe that in the future I will have fruitful collaborations not only within the artistic community but also with people from other professions. For me, art is often about approach and vision rather than about paint and color.

I change materials not only because of the idea but also because of my own perception of the material itself. It’s a kind of exchange: I understand painting better when I make a ceramic sculpture, and I understand graphics better when I work on a large oil painting.

Alexander Kryzhanovskyi

The JI: You work across painting, graphics, sculpture, ceramics. How do you decide which medium a particular idea deserves? Have you ever felt constrained, or liberated, by a medium that you have chosen?

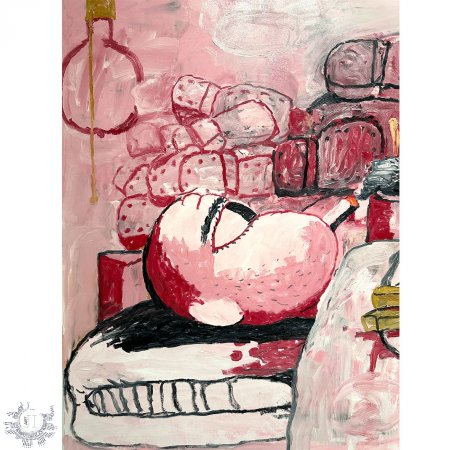

Alexander: In my practice, the notion of an idea is composed of half of what I imagine and half of what emerges in the process. Often, my work begins precisely with what arises during the act of creation – the unpredictable potential of a form or object is what makes it especially engaging for me to work with.

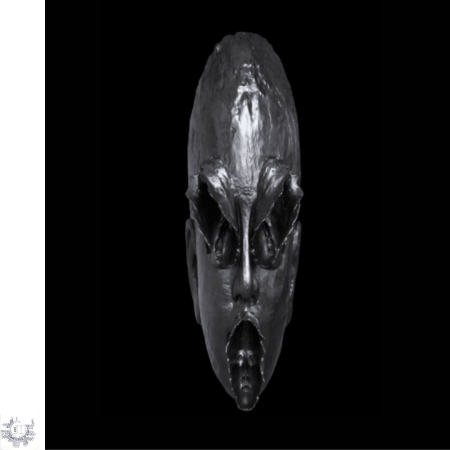

I change materials not only because of the idea but also because of my own perception of the material itself. It’s a kind of exchange: I understand painting better when I make a ceramic sculpture, and I understand graphics better when I work on a large oil painting. This list keeps growing as I continue to explore new and meaningful possibilities within different materials.

I believe that the technical constraints and challenges of materials prevent the artist from slipping into quick production of works made for fast sale, without quality, thought, or depth of observation.

Alexander Kryzhanovskyi

I feel both liberation and constraint in my work. Sometimes the material dictates these things on a technical level, but I see them as interconnected. For instance, sculpture has its own limitations – it dries quickly, is fragile, and can deform – yet these very qualities help me interact with the material without violating its unique nature. The same goes for oil painting: it dries slowly, is difficult to layer, and achieving the needed color intensity requires several coats of paint, stretching the process for at least three or four weeks. I don’t try to change this; instead, I adapt to the material and build a complex communication with it.

When some artists tell me they dislike oil paint precisely because of these qualities, I respond that perhaps I also don’t like them – but I find great value in them. I believe that the technical constraints and challenges of materials prevent the artist from slipping into quick production of works made for fast sale, without quality, thought, or depth of observation.

The first time I visited his studio in Lviv, he turned on a slideshow on his computer and simply said, “Watch.” When it ended, he handed me a primed cardboard and a pencil and said, “Draw.” I asked, “What should I draw?” and he replied, “You already have everything in your head. Just draw and it will appear.”

Alexander Kryzhanovskyi

The JI: I understand that you come from a family with no connection to art. When did you first realize art was something you could or should do? What artists, writers, mentors, experiences shaped your earliest style, and how do they still echo in your work (or not)?

Alexander: When I was about 18 to 20 years old, I began to take an interest in literature – I read a lot and wrote down my thoughts. That was the beginning of my exploration of self, a time when it became necessary to take responsibility for my own life.

At first, I wrote down my ideas and reflections; later, I discovered Kierkegaard, Cioran, Kant, Nietzsche, and Schopenhauer – whose works made me contemplate human existence, morality, and both individual and collective crises.

Over time, I felt the desire to find my own tool for recording ideas and knowledge – something that would allow what I had learned to go beyond theory and text, to take a visual form of interaction. I wanted this to become not only my way of reflection but also a tool for social communication. That was when I became drawn to visual art.

My early attempts to study painting and drawing on my own were not very successful, and I began to realize that I needed a mentor – but it had to be someone who devoted their entire life to art, and nothing else. I wanted to see the broader perspective of what it means to be an artist in the real world, and for that, I needed a living example.

During that time, I was living in Lviv and working at a wine restaurant. I met many artists and teachers from the art academy, as well as musicians and photographers, and some of them became close friends to whom I showed my first drawings.

Among them was the Lviv-based photographer Serhiy Mykhalkiv, who one day introduced me to his old friend, the painter Serhiy Matyash – the person who, from our very first meeting, opened art to me and helped me find my direction of observation and artistic expression, which continues to evolve to this day.

Serhiy Matyash was an artist from Eastern Ukraine, from the Donetsk region – now occupied. He was born there in 1971, received his first art education there, and later moved to Lviv, where he earned a second degree in monumental art and restoration. He was a person with a special sense of reality and an understanding of his own difficult fate – a natural-born master of his craft.

The first time I visited his studio in Lviv, he turned on a slideshow on his computer – a selection of his photos from Crimea, along with paintings and drawings by various artists – and simply said, “Watch.” When it ended, he handed me a primed cardboard and a pencil and said, “Draw.” I asked, “What should I draw?” and he replied, “You already have everything in your head. Just draw and it will appear – let it start, for example, with a seascape.”

That day, I created three beautiful works, and when I looked at them, I couldn’t believe they had just come from my hand. That’s when I understood how association and memory work. I still use many of the methods he showed me – or those I managed to observe while watching a true artist at work, who valued above all the ability for creation and independence.

As for other influences, a large part of them comes from the literature I explored in search of a fundamental basis for my artistic practice. They are not particular people, but rather historical periods that interest me – for instance, Ancient Egypt, especially during the New Kingdom; early Christianity, particularly the Gnostic movement; and the mystical traditions of the Middle Ages, along with their traces in the Renaissance and Reformation. All of these serve as the visual foundation of my artistic search.

I believe that any form of art is political by nature, just as any individual acting within the coordinates of their identity, roots, and memory.

Alexander Kryzhanovskyi

The JI: Do you see your role as an artist purely expressive and personal, or also political, social, or pedagogical? If so, how do you balance those impulses, and how do viewers’ responses and reactions impact you and your work?

Alexander: Perhaps I practice art precisely because the world is complex, intricate, and unpredictable. I believe that any form of art is political by nature, just as any individual acting within the coordinates of their identity, roots, and memory.

As a young contemporary artist, I explore these questions through experience, change, communication, and observation. For this reason, I often describe art as my most essential tool for interacting with the outside world – a tool that is capable of both exerting influence and receiving it.

I wouldn’t call these things “impulses”; they are more like complex categories that are difficult to ignore. For example, I also currently teach academic drawing at an art academy in Kyiv and am beginning work on a doctoral thesis. This experience allows me to engage with art from both a scholarly and educational perspective, interacting with younger generations as well as experienced adults who assist me in my research.

What I receive from people is more than just feedback – it is interaction, an opportunity to bring out new perspectives on art in my practice, as well as a way to understand the current state of culture in the environment where I operate.

Still, I cannot confidently say that these influences are fundamental for me. When I first began practicing art, I clearly understood that I would pursue it under any circumstances, regardless of the trials and difficulties I would likely face.

Of course, like most artists, I am sensitive to nonconstructive criticism and harsh remarks about my work. In those cases, I always try to engage in dialogue and understand the reason behind it. I find this a particularly interesting experience, and I can say that usually, I manage to build good relationships with nearly everyone who engages with my art.

I also have a desire to explore video art and audiovisual projects, though I somehow feel that these work best as team collaboration – for example, developing a shared idea with a team where each person is responsible for a specific function, such as text, sound, space, visuals, dialogue, and interaction with the audience.

Alexander Kryzhanovskyi

The JI: Where do you see your work in, say, ten years? Are there themes you want to explore that you haven’t yet, or forms or media you’d like to experiment with?

Alexander: Specifically within a ten-year timeframe, I hardly can plan my work in detail. But in the near future, I see an expansion of collaborative opportunities – exhibitions, collaborations, experiments with different media, and so on. Before the full-scale invasion, I was working on connecting with curators and art dealers abroad, and I had some plans for solo exhibitions overseas, particularly in the UK, Italy, the U.S., Greece, and Spain.

Unfortunately, I was unable to realize these plans because the invasion had a shattering effect on me, both mentally and physically.

Later, I moved to Kyiv and was able to resume my practice. Almost two years later, I can confidently say that I am actively working to have the opportunity to show my work internationally. Just a few weeks ago, we completed a wonderful project at viennacontemporary with my friend and fellow artist Vasyl Tkachenko, as well as curators Nataliia Tkachenko and Yana Sviderska. It was a great collaboration, and we received a lot of positive feedback and collaboration proposals.

Regarding the media, I want to experiment more with sculpture, and I am currently looking for an additional studio to explore this medium. I am interested in many materials, such as wood, metal, glass, and clay, and I would like to try creating large-scale objects that could complement my artistic expression, which has so far primarily taken place through painting and graphics.

I also have a desire to explore video art and audiovisual projects, though I somehow feel that these work best as team collaboration – for example, developing a shared idea with a team where each person is responsible for a specific function, such as text, sound, space, visuals, dialogue, and interaction with the audience. So, perhaps it can be said that I am interested in collaborative experiences, which could be something new and particularly valuable for me.

During wartime, we lose not only our most valuable people but also our most precious cultural heritage. Many artworks have been stolen as a result of the Russian occupation, others were destroyed in shelling, and many works by contemporary artists may become scattered around the world. Without a digital archive, it would be difficult – even decades from now – to grasp Ukraine’s vast cultural layer, which requires careful attention to ensure it remains part of history.

Alexander Kryzhanovskyi

The JI: UFDA (Ukrainian Fund of Digitized Art) has been archiving many works of art. What do you think about artistic legacy in a digitized era? What do you want digital surrogates to misrepresent (i.e., what should never be fully capturable) so that seeing the original remains necessary?

Alexander: I think UFDA’s initiative to digitize artworks is, first and foremost, a demand of our time. During wartime, we lose not only our most valuable people but also our most precious cultural heritage. Many artworks have been stolen as a result of the Russian occupation, others were destroyed in shelling, and many works by contemporary artists may become scattered around the world. Without a digital archive, it would be difficult – even decades from now – to grasp Ukraine’s vast cultural layer, which requires careful attention to ensure it remains part of history.

This is precisely what UFDA is doing, and I have contributed mainly works that are either already in private collections or will soon be exhibited or sold. It’s a great opportunity for me to be part of an archive where I can view my work in excellent quality at any time.

I believe this does not compete with the originals, because physical interaction with a work cannot be completely replaced by a digital copy. This becomes clear when visiting any museum in the world, a private collection, or even an artist’s studio.

The loss of direct contact with the tangible world is not limited to artworks; it happens in everyday life, in human needs, through the minimization and global simplification of everything around us. I would like visual art to have the ability to reconnect people with their desire to explore and create – just as it did in the cultures of ancient civilizations, and even centuries ago.

Thus, this is a very complex issue, touching on religious, political, evolutionary, and scientific aspects in addition to the cultural. I could share more thoughts on it, as it deeply intertwines with the themes I work with – perhaps in one of our next conversations.