THE SEDUCTIVE AND FRIGHTENING, TENDER AND VORACIOUS MONSTERS OF MARGAUX COMPTE-MERGIER

Perhaps an interesting stance would be to reject the ideal of absolute mastery sought by certain scientific ideologies and instead establish a positive dialectic with chance?

Margaux Compte-Mergier

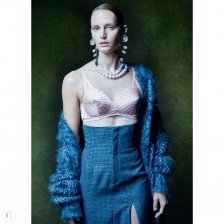

Born in Paris in 1994, Margaux Compte-Mergier is a sculptor, performer, and author whose hauntingly hybrid creatures blur the boundaries between the organic and the artificial, the digital and the mythological. Based between Berlin and Paris, and with a background in the theory and practice of language and the arts (EHESS, Paris), she is currently represented by RÍO & MEÑAKA gallery, and has exhibited widely across Europe and Mexico, with recent solo shows at Tignous Contemporary Art Center in Montreuil and Exgirlfriend Gallery in Berlin.

Margaux's practice is marked by a fascination with transformation, digital glitches, and the aesthetics of chance. She creates what she calls "monsters that hold together our contradictions”—tender and voracious beings made of resin, metal powders, and everyday detritus. As she herself pointed out during our conversation at her recent exhibition at ARCO Lisboa, "they are a bit creepy but also kinda cute".

With a poetic yet unsettling visual language, her work engages with ecological anxieties, posthuman imaginaries, and the precarious beauty of failure.

In this interview, we speak with Margaux Compte-Mergier about material fragility, the seduction of digital errors, and the role of art in navigating a fractured, unstable world.

I create monsters that hold together our contradictions; these creatures are both seductive and frightening, tender and voracious.

Margaux Compte-Mergier

The JI: Your sculptures often merge organic and synthetic elements, creating a sense of familiar strangeness. How do you deal with this boundary—between the natural and the artificial—in your work? What does this interplay mean for you?

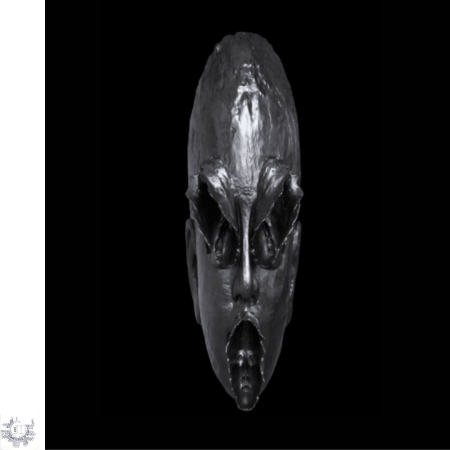

Margaux Compte-Mergier: I would say that my sculptures always represent a moment of transition, an intermediate state of transformation suspended between the vegetal, the animal, the body, humans, everyday objects, and the digital.

There are several aspects of these hybridizations that interest me. I create monsters that hold together our contradictions; these creatures are both seductive and frightening, tender and voracious. They embody our fears and dreams. They present an imagery of DNA experiments, ecological catastrophe, and war, while also pushing the boundary between the natural and the cultural by presenting beings that, despite all the disasters, find a sense of wholeness. They confront several serious contemporary issues without extinguishing all hope.

I’ve learned to engage in a dialogue with the randomness of nonmastery.

Margaux Compte-Mergier

The JI: Your art deals with the concept of ‘digital errors’. Could you explain how the aesthetics of digital glitches influence your creative process and the stories that you want to tell?

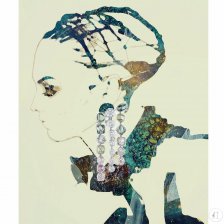

Margaux: What particularly interested me with the emergence of generative AIs were their moments of failure—especially in image production. There was something that resisted the pure logic of the system. “Bugs” that once again allowed a chance to enter the equation. These errors produced a kind of "remainder," something irreducible that often led to strange and unpredictable forms. In my sculptures, there is a desire to evoke this free aesthetic of sudden randomness.

Following this reflection, digital errors also gave me—strangely—hope, and they helped me revalue mistakes within my own creative process (in which AI is not involved): of course, I often control my creative gestures, but there are regular slips: suddenly, I no longer control what I’m doing. The material or form escapes me and leads me somewhere I couldn’t have imagined without the intervention of chance. It makes me rethink the composition of the sculpture I’m working on, and the next gesture becomes a response to the mistake—not to erase it, but to sublimate it. I’ve learned to engage in a dialogue with the randomness of nonmastery.

This opens a broader perspective on our contemporary world—faced with everything we do not control: nature, genetics, political crises, and more.

Perhaps an interesting stance would be to reject the ideal of absolute mastery sought by certain scientific ideologies and instead establish a positive dialectic with chance?

The JI: Your work often addresses the themes of catastrophe and future projections. How do you perceive the role of art in engaging with societal anxieties about the future? What responsibilities do artists have in this perspective?

Margaux: I see art as a means of opening a pathway for reflection on our contemporary world. For me, artistic creation should bring together themes that raise philosophical and ethical questions. It is not about delivering judgments or readymade answers, but

rather about opening up questions—creating spaces into which viewers can step in order to build, in relation to the work, their own thinking about the world.

The role of the artist is therefore to remain deeply connected to the multiple issues of our time and to work towards creating meaningful forms that open up a dialectic.

The everyday objects I use are archetypes; I choose them to be as simple and neutral as possible. What particularly interests me about these objects is that they speak of our seemingly mundane practices, our small gestures. But when we look at them differently, they form an intimate portrait of our culture.

Margaux Compte-Mergier

The JI: Incorporating everyday objects into your sculptures transforms the mundane into the extraordinary. What draws you to these objects? How do you select them to convey specific meanings or emotions?

Margaux: The everyday objects I use are archetypes; I choose them to be as simple and neutral as possible. What matters is that they give each viewer the feeling that the objects could belong to them. They do not bear the marks of a specific relationship but instead carry the potential for a relationship with anyone.

What particularly interests me about these objects is that they speak of our seemingly mundane practices, our small gestures. But when we look at them differently, they form an intimate portrait of our culture. We are so used to living with them, using them, seeing them, that we forget their shapes, their aesthetics, the meaning of their existence. I worked with these ordinary objects by altering their material, creating encounters with other elements—I wanted to provoke the surprise of aesthetic strength within the banal, to renew our gaze so we might rediscover, in what surrounds us, a trace of our history and of our deep rootedness in a present that they weave together with us.

In a way, it was about trying to spark the kind of estranged gaze we might cast, for example, on the objects preserved in lava in Pompeii, but within our most familiar intimacy. I realized that this renewed way of seeing often creates a gentle feeling of melancholy, due to the distance it introduces from our present. Sometimes that melancholy blends with a sense of amusement brought on by unusual displacements. It’s a state that seems to me especially fertile for questioning everyday practices.

Many of my colors come from a blend of bronze and iron powders. These are colors in flux—they’re not stable, because the metals react with the humidity and acidity of the air. Over time, the colors shift slightly, they oxidize. This is something I really like, because I don’t control this transformation—the sculptures continue their lives without me.

Margaux Compte-Mergier

The JI: Your choice of materials in your sculptures is very distinctive, often using industrial objects alongside natural elements. Could you tell us more about these materials and their physical, philosophical, ethical, and artistic significance in your work?

Margaux: The primary material I use is a natural resin made from stone powder. I then mix this resin with metal powders, pigments, and soil. Many of my colors come from a blend of bronze and iron powders. These are colors in flux—they’re not stable, because the metals react with the humidity and acidity of the air. Over time, the colors shift slightly, they oxidize. This is something I really like, because I don’t control this transformation—the sculptures continue their lives without me.

Of course, the encounter between natural and industrial elements opens up the idea of a possible coexistence, of another form of life yet to be imagined. I believe we have

much to learn from other ways of thinking about anthropology. Philippe Descola, among others, has shown us the existence of different relationships between the “natural” and the “cultural” in certain human societies—relationships that do not set up oppositions but instead create continuities.

The JI: Your practice incorporates sculpture, performance, and writing. How do these disciplines work together in your creative process? How does each medium contribute to the overarching themes you explore?

Margaux: That’s a very good question! In all my practices, I’m interested in the same core questions. But each medium I work with requires a specific kind of attention to its own properties. In the initial stages, my texts tend to follow a more linear logic, whereas my sculptures—on the contrary—develop through a plural, simultaneous logic that I then need to organize.

Moving from one medium to another allows me to introduce visual art perspectives into my writing, and vice versa.

Because we initiate processes, creation remains possible—never finished, never sufficient, never entirely satisfying. It’s this that will keep me alert to the world for the rest of my life.

Margaux Compte-Mergier

The JI: Being an artist is often described as both a privilege and a challenge. What does it mean for you to be an artist, and how do you navigate the complexities of this identity in your day-to-day life?

Margaux: As an artist, one opens up a field of research—whether by choice or perhaps because it chooses us—and this brings daily richness, a direction for the life of thought. My way of honoring this privilege is through relentless, daily work. It is in this labor that both the privilege and the challenge converge.

Because we initiate processes, creation remains possible—never finished, never sufficient, never entirely satisfying. It’s this that will keep me alert to the world for the rest of my life.