Engineering and design, tradition and the avant-garde: this is grima london

Several people would qualify for the title of father of modern fashion. But then there is just one person who can unequivocally be called the father of modern jewelry.

His name is Andrew Grima.

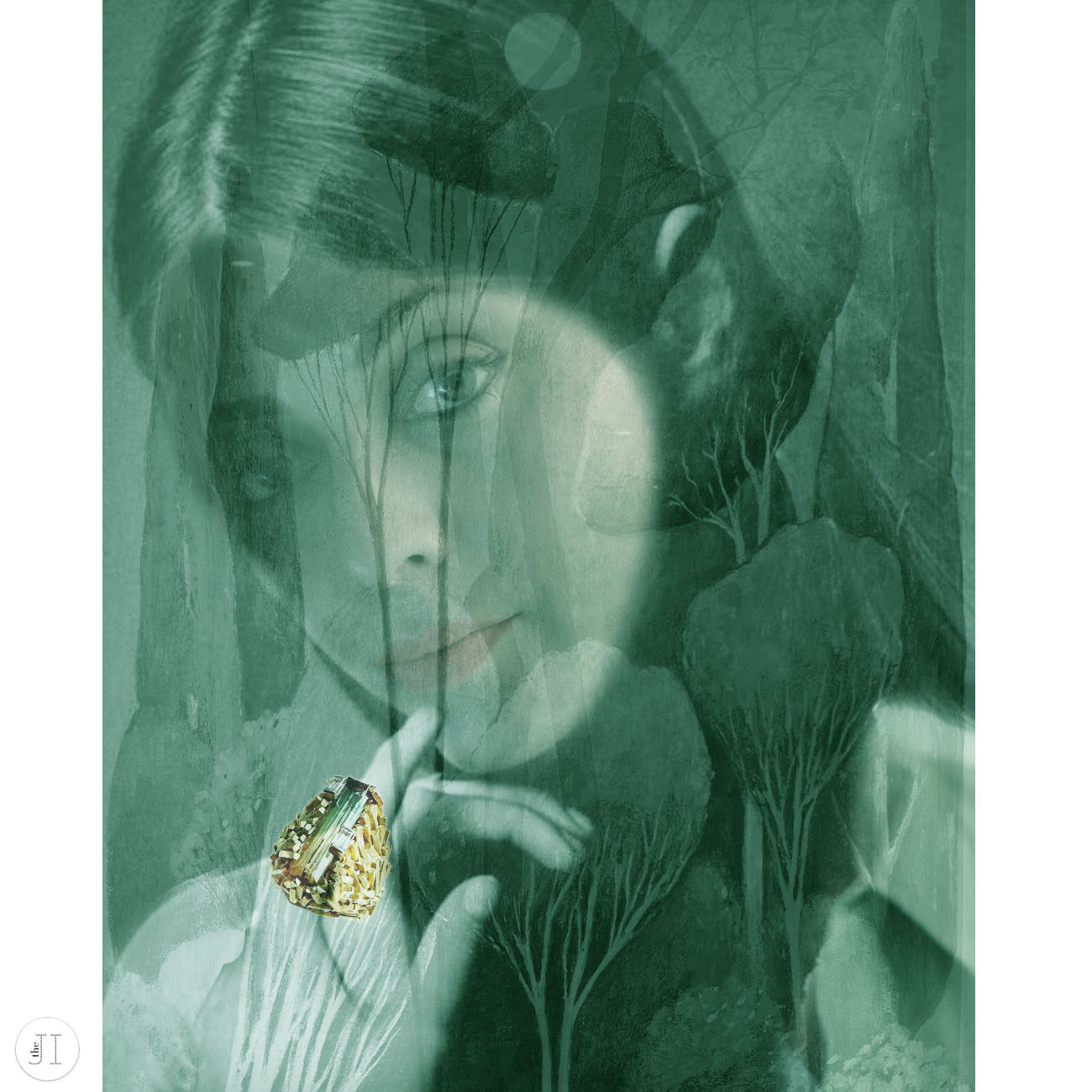

Grima’s style cannot be mistaken for anyone else’s.

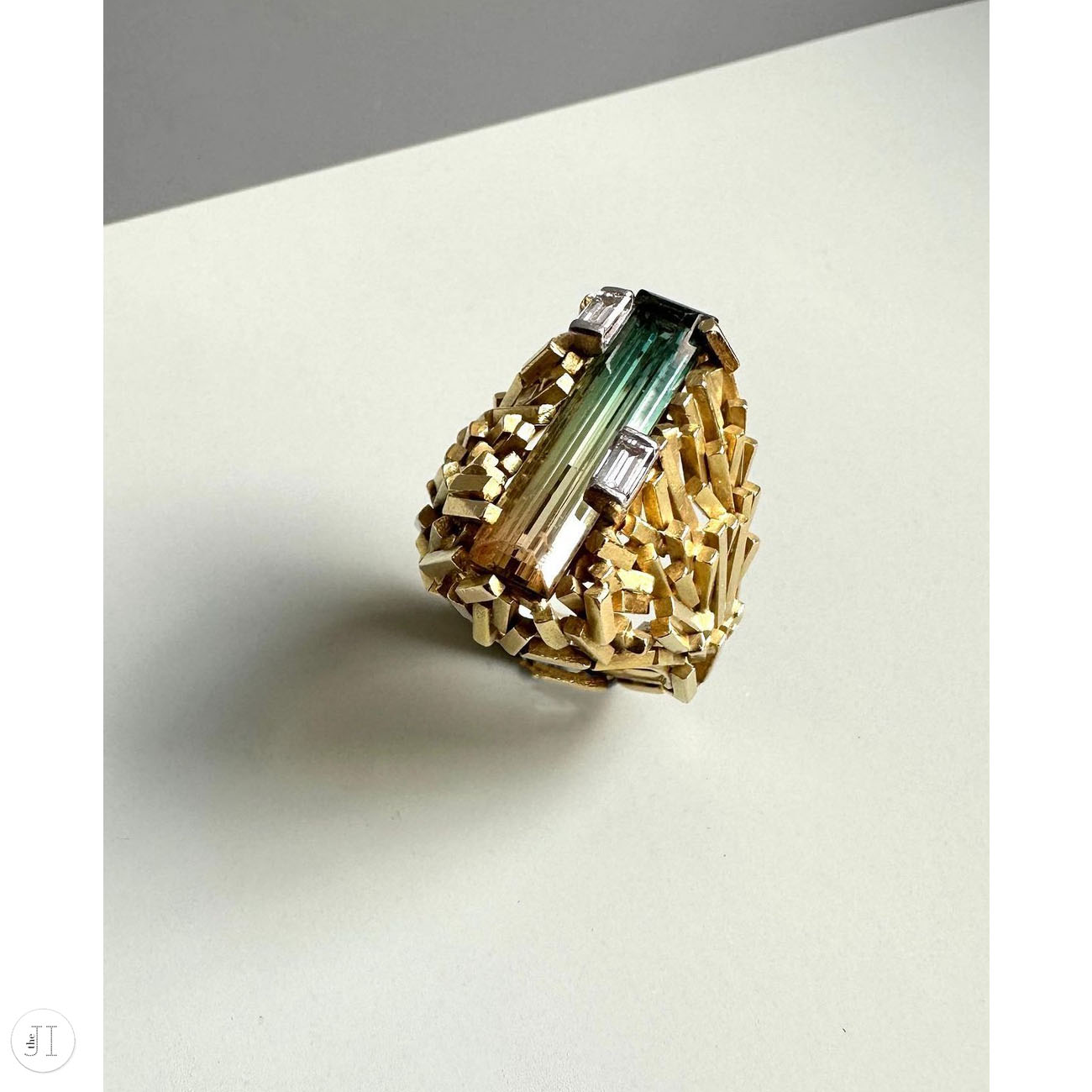

This ring, designed by him, comes in the shape of yellow gold “matchsticks”, or prolonged bricks, set with baguette-cut diamonds, surrounding an exquisite, bi-coloured tourmaline. The fundamental nature of bricks is contrasted disobediently with sumptuous chaos, creating an incredible synergy of movement.

The ring comes from one of Andrew Grima’s bold and innovative 1970s collections which changed the face of post-war British – and all contemporary – jewelry into pieces that are bound to become the focus of attention and require of the wearer both a high level of self-confidence and attitude.

The aesthetics of that decade were a hodgepodge of styles in fashion, music and art. From Marvin Gaye, who helped shape the sound of Motown (a style of rhythm and blues), earning the nickname “Prince of Soul”, – to the inimitable David Bowie. From wide, pointy collars and stylistically questionable double denim – to Vivienne Westwood who, at that time, was the icon of Punk, and Yves Saint Laurent who, during the ’70s, was developing his own unique voice.

Andrew Grima’s personality and creative journey are too multifaceted to fit within the frame of a single story. But we invite you to join us in discovering the chapters of his life through some curious facts about this colorful artist and designer.

An engineer turned designer

Andrew Grima was not a jewelry designer by training. Born in Rome in 1921 into a Maltese-Italian family that later moved to London, he spent his childhood days happily drawing and sketching. The rest of his family was also artistic: his father was an embroidery designer; his brothers George and Godfrey became architects, later helping to design Andrew’s unconventional London showroom.

Andrew studied mechanical engineering, Then, during WWII, he volunteered for the British Army. When the war ended, he wanted to pursue his passion for drawing, but most art colleges were still closed. So he entered a secretarial course, where he met his wife Helène and later joined the accounts department of her family’s jewelry business.

Two years later, a life-changing moment occurred. As he himself recalled, “two dealer brothers arrived at our office with a suitcase of large Brazilian stones – aquamarines, citrines, tourmalines and rough amethysts in quantities I had never seen before. I persuaded my father-in-law to buy the entire collection and I set to work designing. This was the beginning of my career.”

Andrew Grima’s daughter Francesca remarks that not being a designer by training must have helped him create some of his most daring and revolutionary designs. He did not have the narrowmindedness that might have made him think: I have to design jewelry that looks like jewelry. Rather, the combination of technical drawing skills and his love of art proved crucial in Andrew’s original, creative toolbox.

The bizarre shops of an unusual personality

Andrew Grima’s shops in themselves were original works of modern art.

He opened his first shop in 1966 on Jermyn Street in central London. By 1986, it was demolished and replaced with an unremarkable façade. However, in its golden days, the shop was a majestic, if not outrageous, structure.

Its exterior, designed by Bryan Kneale, took the form of a large screen, where huge, rough pieces of slate were attached to a metal frame. Instead of large glass windows, which you would expect from a standard jewelry boutique eager to showcase its merchandise, there were narrow peepholes and openings through which curious passers-by could gape at the unusual masterpieces.

Hidden behind the massive, automatic, aluminum door, designed by Geoffrey Clarke, there was a two-storey interior, designed by Ken Adam, a translucent perspex spiral staircase, engineered by Peter Rice, and Andrew Grima’s office – a white, concrete, tube-shaped bunker – located right in the center of the room.

A decade later, building on his reputation as an extraordinary personality, artist and businessman, Andrew Grima opened another jewelry shop in Zurich. This time, his two architect brothers used the salvaged hull of an old clipper ship as the foundation of the shop’s head-turning façade.

"Disrespect" for diamonds

Andrew Grima was not one to obsess about precious stones. A rebel in the world of jewelry, he refused to put a million pound-worth diamond or ruby on a pedestal and treat it differently from a cheaper, “imperfect” mineral or riverside pebble. Rather, he liked original, semiprecious gems, often in their raw, uncut form, which he would then offset and highlight with minimalist diamond or sapphire accents.

The same goes for the purity of gemstones: building his designs around natural wonders, with their natural inclusions, imperfections, and mischievous characters, he firmly believed that a masterpiece is, first and foremost, valued for its design and artistic message, rather than for the monetary value of the stones and metals used in it.

Today, the Grima brand continues to follow in the footsteps of its founder, with each stone exactly and strictly in its place. For example, the dioptase used in the production of a stunning necklace in 2020 waited in the Grima gem and mineral collection for 34 years for its moment of glory.

The Royal Jeweler

In 1966, Prince Phillip bought a “Venus” brooch – carved rubies in yellow gold – for Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth. Soon afterwards, Andrew Grima was awarded the Duke of Edinburgh’s Prize for Elegant Design and the Queen’s Royal Warrant, and in the decades to come, he designed over a hundred masterpieces for the Royal Family.

He also became Britain’s first celebrity jeweler. Alongside royalty, his clients included Jacqueline Onassis and Estee Lauder and, among contemporary wearers, Miuccia Prada, Marc Jacobs and Gwendoline Christie.

Watches with precious faces

In 1970, Omega – the Swiss luxury watch company – commissioned Andrew Grima to design and manufacture an exquisite collection of dress watches which, to this day, remain unrivalled in their game-changing, powerful design and clever implementation.

At a time when digital watches seemed to endanger the art and craft of making complex, mechanical watch movements, Andrew Grima’s About Time collection displayed time through glass-like precious gemstones. For that purpose, stonecutters had to cut precious and semi-precious stones into odd shapes and sizes, and jewels faced the ultimate test of their skills.

Six years later ,Andrew Grima designed another revolutionary collection of solid gold digital LED watches for Pulsar – the inventors of the electronic digital watch.

A legion of awards

Andrew Grima was the only jeweler to win the Duke of Edinburgh Prize for Elegant Design. He also won eleven prestigious De Beers Diamonds International Awards – more than any other jeweler in the history of those trophies.

The irony of the moment

On 25 December 2007, Queen Elizabeth II wore her Grima ruby and diamond brooch – a gift from Prince Philip – while delivering her Christmas Message.

Andrew Grima, the most significant, influential and spectacular jewelry designer of the post-war period and the father of modern jewelry, died the following day, at the age of 86.

Wherever he found himself, he was constantly designing, sketching on hotel notepaper, drinks coasters and the back of menus.

Nicholas Foulkes, The Telegram